“Suppose you are a woman, happily married, that you have a 21-months-old daughter, and that you know something valuable to the state in a murder trial; but that to reveal what you know will turn a shadow of rumor and suspicion upon yourself and probably cost you your future happiness, your husband and your child. What would you do?”

That moral dilemma is from a July 9, 1923 San Diego Sun article by Magner White about a conflicted witness, Army nurse Blanche Y. Jones, and the murder trial of Army physician Dr. Louis L. Jacobs who was arrested for the salacious death of “Miss Fritzie Mann, a pretty, young San Diego dancer in a delicate condition.”

Magner White could certainly turn a phrase. He was a resourceful and clairvoyant reporter with the ability to dip his pen into the future. After spending the summer of 1923 covering two jury trials (one “hung” and the other “not guilty”) for Dr. Jacobs, White would face a perplexing situation of his own.

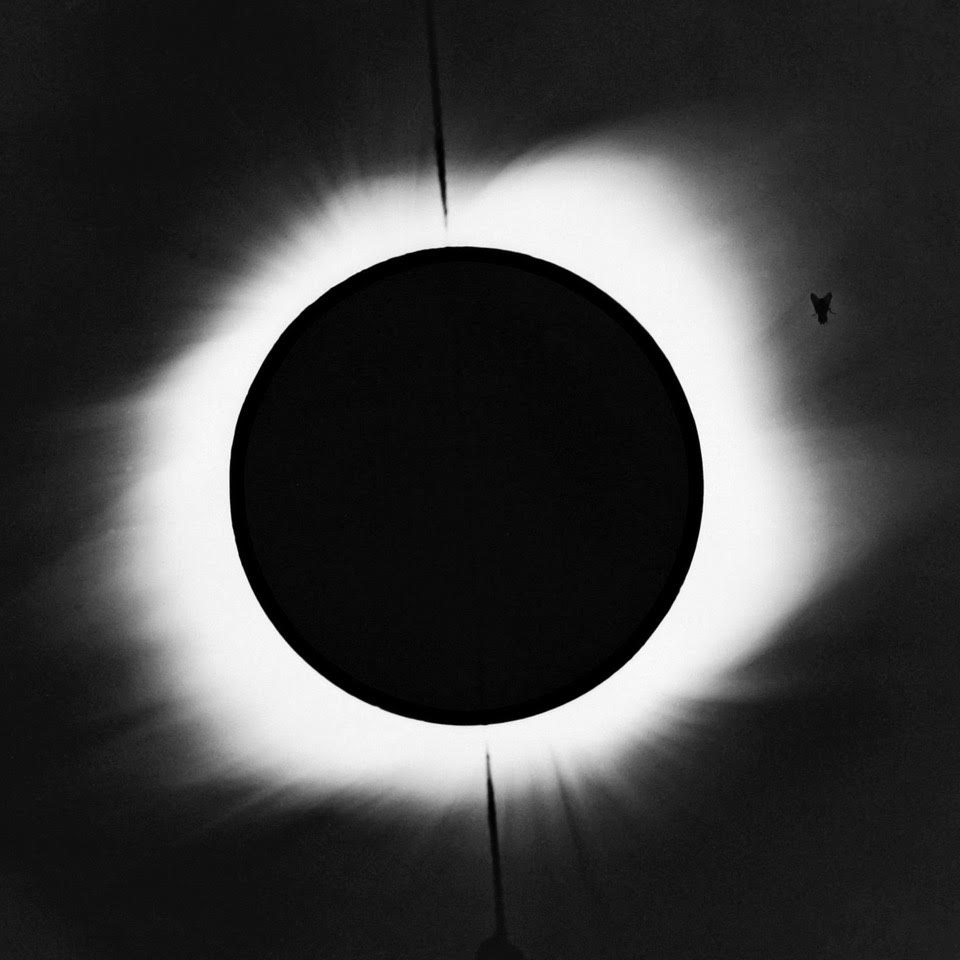

The Sun was an afternoon newspaper. His editor assigned him to cover a total eclipse of the paper’s namesake scheduled for noon on September 10, 1923. How could he write a story in time to hit the streets that same afternoon? What would he do?

White was well aware that most accounts of solar eclipses were dull and uninteresting. He knew that he could do better. His lengthy, highly-detailed article headlined, “When it was midnight at midday!” is condensed with these excerpts:

“The biggest shadow in the world — 235,000 miles high, 105 miles wide, and 75 miles thick in its densest part — fell across San Diego today, the shadow of the moon as it crossed the face of the sun. The heavenly appointment was carried out as predicted, 120 years since the last time, 120 years until the next time.

One hundred and twenty years ago, scared Indians fled over the hills at the sight, or the more civilized ones knelt before the shrines in the comparatively new San Diego mission and received the comfort of padres, wise in the mysteries of the heavens.

Chickens, puzzled by the abrupt night, took to their roosts; and cattle stirred restlessly in the yards, the routine of their lives distorted by the happenings in the sky. Animals in Ringling Brothers circus, waiting for the afternoon performance, paced their cages and roared and whined, disturbed by this sudden lighting up within a few hours of morning.

Noon whistles sounded — the first time a noon whistle ever sounded in San Diego during a eclipse of the sun. Midnight at midday! Paradox of 120 years. But this is terrible awe. Children on the doorsteps catch it and cry out in the darkness.

By telephone we get a picture of ‘Quaint Tijuana’ during these three minutes. There is no wickedness there now.

The saloons have no customers during this sample of absolute night. Painted women stand in their doorways and look out on the heavens for the first time, perhaps, in years with wondering minds. Before the spectacle they are moved inwardly with misgivings. The background of childhood superstitions and those years, long ago, of contact with churches comes to the front.

Their poor souls, dormant and obscured by the fast life, begin to scratch inside their broken bodies — and the pain of that passing experience is sweet, because it is so rare.

Ah, it’s lighter now. The gloom is passing. It lifts, speeds by, and again the shadows are lacy. Soon it is morning of the ‘night that came in the day.’

Puzzled chickens flock down from their roosts. Cows go back to their grazing. Street lights are turned off. Frightened children are reassured. San Diego drifts back into its marts and households. Tijuana shakes its languor.

The spell is gone, gone for 120 years. When the shadow returns, we shall not see it. We shall be with the Pala Indians of 1806.”

If you enjoyed that story, you’re not alone. It won the 1924 Pulitzer Prize for Journalism, the first time the award went to a reporter of a newspaper located west of the Mississippi River.

The judges wrote, “in writing about a solar eclipse… Magner White turned what could have been an ordinary story into a masterpiece… White does a masterful job of providing a moment-by-moment report.”

The long-defunct Sun has been described as “the third newspaper in a two newspaper town.” Today, if the Sun is remembered at all, it is for covering San Diego’s waterfront and, in the parlance of a good waterfront reporter, there was something fishy about White’s tale.

In 2004, former U.S. congressman and Sun reporter Lionel Van Deerlin laughingly told columnist Don Bauder that for reporter White to beat his deadline, “the story was written in advance of the eclipse.”

Tony Perry wrote in a May 22, 2012 Los Angeles Times article that a colleague described White as “a very polite con man and a great reporter.”

The Sun editor who had assigned the eclipse story said, “Magner White was a damn fine newspaper man,” but added, “He got cocky after winning the Pulitzer though.”

“A third Sun alum: ‘Magner used to joke about never having to leave the office to win a Pulitzer.’”

Magner White’s fanciful article may have been the first fraud to win a Pulitzer, but it wasn’t the last…

Janet Cooke won the Pulitzer in 1981 for “Jimmy’s World,” a tragic story about an eight-year-old heroin addict in the Washington Post. When her credentials fell apart, she admitted the article was fabricated. Cooke was forced to resign and return the prize.

Subsequently, there have been several high-profile examples of fraudulent journalism and plagiarism involving controversial contemporary issues. We now live in the so-called “information age.” Cable news, social media and political commentary spawned the concept of “fake news.”

Magner White’s eclipse story from 1923 is funny and harmless.

Fake news is not. It eclipses truth.